When I first begin digging for water facts in 2018, things were different, so I will try to update as I go, here.

One of the most talked about subjects in Yavapai County, AZ is water. News media on both sides of Mingus Mountain tend to use the most sensational statements about water nearly every month because the squeaky wheels get the most grease (or media play).

Mingus Mountain is important because it causes a major water source on both its northeast and southwest sides to change course. And the squeaky wheels have been forming committees for several years in order to discuss how much water is in the Verde River before it collides with Mingus Mountain, and later, when it runs through Clarkdale, Cottonwood, Camp Verde and becomes a Phoenix water supply.

Some entities have taken action. Some have not.

Naysayers will tell you with thousands of building permits being granted by Prescott and Prescott Valley that water will run short. But municipalities cannot grant building permits unless the subdivision plat has obtained a 100-year Assured Water Supply from the State.

“It’s not as simple as saying we are running out of water, or not running out of water, or is there enough water,” said Jamie P. Macy, Supervisory Hydrologist, at the United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) Arizona Water Science Center, in Flagstaff.

Macy refuses to “get sensational” like the multitude of water study committees because we just don’t know how much water we have, yet. Golder Associates, Inc. has been hired under contract with City of Prescott, Prescott Valley and Salt River Project to construct a detailed groundwater model for an enormous sub-basin of water near Paulden, AZ. The model and its report are due in May of 2020.

Not long ago, four water committees in Yavapai County were working on the same issues at the same time and some municipalities had to pay to join. They all differed on how much water the county had, members harped about lack of rain, and most members were motivated by stopping growth such as commercial and residential building.

author Bill Williams standing at the confluence of the Verde and Salt rivers

THE CAMP VERDE SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN

“Claiming that we are running out of water is a viewpoint touted by a number of small activist groups, but is not the majority viewpoint,” said Cottonwood Water Resource Manager and former Arizona Department of Water Resources manager Tom Whitmer. “What makes these claims difficult to deal with is that many of the claims being made that sections of the Verde River will go dry in the next 10-to-20 years are being made by seemingly credentialed individuals who tend to get lots of space in the newspaper. For many, stopping growth seems to be the ultimate goal and the only tool at their disposal to stop or slow down the growth is the river.

“Stopping growth through the legislative or planning and zoning process has thus far proved futile so the only other means at their disposal is to convince people the river is going dry as a result of pumping in the hopes that it might dissuade others from moving here.”

Cottonwood was a member of the Yavapai County Water Advisory Committee, before it was terminated by the County. Whitmer now relies on sound research and methodology when he describes the water trove near Paulden known as the Big Chino Sub-basin, and the Verde Valley as having enough water to keep Verde Valley residents in water for hundreds of years, even if it never rained again.

Whitmer can make that claim because estimates of water in storage in the basin down to a depth of 1,200 feet by the USGS and ADWR have ranged from 13-to-28 million acre-feet. There is a big and little aquifer and estimates for the Big Chino alone have ranged from seven-to-ten million acre feet down to a depth of 1,200 feet and some sections of the basin are as deep as 3-to-4 thousand feet.

To put that in perspective, “The Town of Prescott Valley pumped 5,600 acre-feet in 2017,” said John Munderloh, former Water Resources Manager for Prescott Valley, AZ.

The City of Prescott pumped 6,771 acre-feet,” added Leslie Graser, Water Resource Manager for Prescott. “This is the volume that was reported to the State of Arizona as required in Annual Water Withdrawal and Use Reports.”

The Verde Valley area benefits from the same water shed that recharges the Big Chino, as well as Oak Creek, Beaver Creek, Sycamore, Fossil Creek and West Clear Creek which help supply the Verde River. Only a couple of towns in the Verde Valley provide water to customers. The rest are either served by a private water company or have their own private well.

The towns of Cottonwood and Clarkdale have actually reduced pumping by almost 30 percent over time due to water conservation and upgrades to their water systems, according to Whitmer.

When talking about the use of groundwater, it is important to understand that people aren’t the only users of groundwater. According to Whitmer, the single biggest user of groundwater in the Verde Valley, based on a USGS study, is the riparian forest that encompasses the Verde River. Whitmer isn’t touting the removal of the riparian forest, but did indicate the removal of some of the woody vegetation in the upper portions of the watershed could potentially be beneficial to the groundwater basin and ultimately the river.

According to Whitmer, the Upper Verde River Watershed Protection Coalition is currently conducting a pilot project to determine the benefits of thinning the woody vegetation such as junipers in the upper portion of the watershed. Studies conducted by a number of agencies thus far have indicated that thinning forests and brush can increase water recharge and enhance runoff.

The problem for Verde Valley residents is not a lack of water. It is determining who owns the water.

“A water rights lawsuit that was filed in 1974, nicknamed “The Adjudication” has 57,000 water rights claims by 32,000 parties,” said Sarah Porter, of the Kyl Institute for Water Policy at Arizona State University.

But with help from the late Joseph Feller – former Arizona State University professor – this reporter was able to track a lawsuit back to 1905 when a farmer near the Salt River filed suit against Indian tribes and other farmers. In stepped lawyers and the Salt River Water Users and voila, the first water right was decreed.

Court records obtained by this reporter show the seemingly “never ending” lawsuit has 78,000 claims and 849,000 summonses were sent out. In 2004 Salt River Project – the Phoenix-based utility which claims water rights all the way to the head waters of the Verde River – filed motions against five water users groups from the Verde Valley.

Porter co-authored the report The Price of Uncertainty. The report says new wells continue to be drilled in areas that stand to be most affected by the Adjudication. And before they drill, land-owners do not receive detailed notice or information that they may not have any right to the water supplies they’re counting on. Real estate development and growth are not the only things impacted by water rights uncertainty.

Some Arizona communities recognize that the environmental attributes of a nearby river or stream make their community special, but until the Adjudication is resolved those communities lack a mechanism for implementing a management plan to protect those attributes.

Arizonans and municipalities might have to enter the lawsuit to be certain. Not all water rights in Yavapai county have been legislated and The Adjudication complicates the legislature’s authority. It is important to note that, by law, Yavapai County government cannot get involved in the lawsuit or in providing drinking water to residents, or even govern water wells in unincorporated parts of the county.

Arizona law has made it very easy to sink your own well on your own property without concern that any government entity is looking at your pump gauge, or even inspecting for arsenic. The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality regulates drinking water standards.

Here was a partial list of entities who believed they had a stake in the Adjudication matters:

- Salt River Water Users Association

- Salt River Project

- Federal agencies

- Copper mines

- Verde River Ditch companies

- Arizona tribes, towns and municipalities

- Friends of Verde River Greenway (Verde River Basin Partnership)

- Upper Verde River Watershed Protection Coalition

You acquire water rights by past use from a river, past pumping from the sub-flow, or the transfer of water rights.

According to Water Asset Management’s website…. In October 2007, the Town of Prescott Valley sold 1,103 acre-feet of effluent water to Water Asset Management, with the option to purchase an additional 1,621 acre-feet that may be made available in the next few years. During an unprecedented, two-day auction, the rights to this water — the only available to meet the demands for new growth in Prescott Valley — was up for grabs to the highest bidder and attracted both local and national interests through the use of a unique price-floor bid process.

By offering these water rights via auction, the town encouraged a competitive-market outcome and was able to generate an additional $14 million in revenue once this public-private partnership was finalized. Some are still shaking their heads over this sale and what a buyback could cost Prescott Valley in 2032.

Verde River near Tuzigoot

Part Two: Is the answer to our water woes the 30-mile long pipe?

Over time, I have sought opinions from the Jon Kyl Center for Water Law at ASU. Sarah Porter is the inaugural director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at the Morrison Institute at Arizona State University. The center is named after retired U.S. Senator Jon Kyl. Porter is an expert on Arizona water law and policy, with a background in both law and natural resource management.

Porter points out that an Arizona Supreme Court stated that water pumped from the ground, and surface water, are legally connected when the pumped water would otherwise form part of the surface or subsurface streamflow.

Yavapai County Judge Mackey and Maricopa County Judge Brain have held hearings in their respective courtrooms, and the Arizona Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court have entertained motions on the water lawsuit. Cochise County Superior Court has also held hearings on the matter. We may not see an end to The Adjudication lawsuit in our lifetime.

Ironically, Prescott Valley’s town attorney wanted to play in the lawsuit and he paid a Phoenix law firm to write a 75-page pleading. The Town filed as a claimant (well owner) in 2020 and began participating as an observer in adjudication hearings regarding the Verde River in 2021. The town submitted comments to an Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) Verde sub flow report in 2022 and participated in oral arguments before a Special Master regarding an ADWR report titled Subflow Zone Delineation Report for the Remainder of the Verde River Watershed on January 22, 2024. The Special Master allowed the Town to intervene as a formal party. Hearings progressed through August of 2024 and a trial has been set for February 2025. The Town cooperated with Prescott, Chino Valley, Arizona State Land Department, Freeport-McMoRan Inc. (global copper miner), and Chino Grande LLC (owner of ranches and water rights) in support of the Report (contesting SRP’s position against the Report). Evidence in the lawsuit includes reports and observations of early explorers from 1829 to 1854, and the case will hinge on whether the Big Chino Wash was flowing in the 1800s or has always been an ephemeral stream that only flows after it rains or snows.

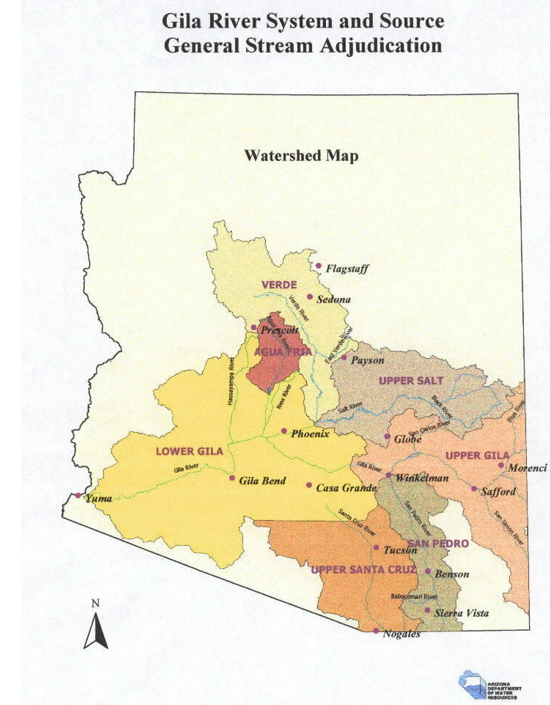

Town of Prescott Valley is impacted in a large way by flows of the Verde River watershed, and legal ramifications of the Gila River watershed. The Gila River comes out of the ground near the Gila Indian Cliff Dwellings in New Mexico, and flows west through Arizona.

Leslie Graser was quick to point out that the city of Prescott has not reached safe yield, as defined by the ADWR and its Active Management Areas (AMAs). Neither has Prescott Valley.

A 1980 law decided that, since we are heavily relying on mined (or pumped) water, we need to aggressively manage the state’s groundwater.

Surface water is what you can see flowing down the rivers and streams. Groundwater is what we pump.

In the Phoenix, Prescott, and Tucson AMAs, the primary management goal is safe-yield by the year 2025. Safe-yield is accomplished when no more groundwater is being withdrawn than is being replaced annually. Clarkdale, Cottonwood and Camp Verde are not currently included in an AMA.

Some entities have taken action. The Town of Chino Valley entered into a unique public-private partnership with Chino Grande Limited Liability Company (LLC) to assure a sustainable water supply and achieve safe yield.

In summer of 2024, the Yavapai-Apache tribe won a major court victory over water rights. The central issue in the $1 billion settlement involves a 60-70-mile-long pipeline that would deliver water from the C.C. Cragin (or Blue Ridge) Reservoir on the Mogollon Rim to the Yavapai-Apache Nation in the Verde Valley, and allow the Nation to limit future groundwater pumping, which is a key factor in protecting flows in the Verde River, according to the tribe’s Chairwoman and The Nature Conservancy. The tribe awaits a final authorization from the federal government.

As we said in Part One, water conservation is very important in Yavapai County, AZ. Since 1999, no developments were granted new groundwater allocations (thus protecting the water supplies for existing homes and lots platted prior to 1999) and the only way forward for new development in the Prescott AMA is to utilize sustainable water supplies such as effluent credits or surface water.

Graser says conservation and an efficient water utility is important and the City of Prescott has an effluent recharge program, along with a tiered rate system – the more you use, the more you pay.

Prescott Valley will even sell you effluent credits if you are a developer who needs to show you have a water supply for the future.

Nearby Granite Creek and Lynx Creek substantially contribute to recharging aquifers. The aquifers described in this report are not large storage pools but should be thought of as heavily saturated gravel beds.

“We have 2.9 million acre feet of water, which is about twice the size of Lake Pleasant, sitting 500 feet below the town of Prescott Valley,” said Munderloh. No one is sure how the town gets that estimate, or how accurate it is.

Although Prescott Valley pumps its water from the large aquifer beneath the town; it indirectly benefits from the Verde River and the Big Chino Basin, if one considers that the watersheds and aquifers of the state do meet up, eventually. The town taps about two dozen wells from an aquifer beneath town. The town shuttered one well when it exceeded federal limits of arsenic, but later, town council approved drilling more wells and money for repair and maintenance of others.

“Six of the town wells are inactive for various reasons,” said Neil Wadsworth,

Utilities Director, Town of Prescott Valley, back in 2018. “The well that has arsenic issues is not considered inactive, but rather out of service. We are in the process of doing some work on it to see if the arsenic can be reduced so that we can use the well again.”

Arsenic is naturally occurring in Arizona aquifers and is also a byproduct of mining.

But now PFAS has been detected in four Prescott Valley area wells and about the same in Prescott; three in PV have been shut down in the Quailwood neighborhood because of PFAS. The fourth one had its PFAS levels go down.

Prescott Valley won an international award for an innovative approach to creating a market for effluent to be used for growth, rather than groundwater. Because Prescott has a much older infrastructure and hilly terrain, it has greater challenges than the newer and flatter Prescott Valley. In fact, Prescott pumps water from six wells in Chino Valley in order to meet its demand.

Munderloh said ADWR monitors over 100 wells in the Prescott AMA and has determined that water levels are declining – a condition that has been occurring since the 1960’s. The AMA was only recharging 10,000 of the 18,000 acre feet that it pumps (in 2018) and according to the 1980 Ground Water Act, “We have to reach safe yield by 2025. The requirement is in the statutes and the Fourth Management Plan. The Big Chino is the only legal source we have to reach safe yield,” Munderloh said.

One problem for all of us is that private wells do not have to be monitored by any governmental organization, according to Arizona law.

Yavapai county has two enormous underground aquifers north of Paulden and south of Seligman, AZ known as the Big Chino and Little Chino aquifers. Yet some “water advisory groups” are quick to claim the Verde River is running dry, and locals will be out of water soon.

The naysayers say Yavapai County residents and towns are pumping too much. Ironically, in a dry season, pumping can result in a cone of depression and actually facilitate an increase in aquifer storage space and create more stream recharge. The naysayers point to a sentence in a year 2002 ADWR report that said the headwaters of the Verde River – Del Rio Springs – will go dry by 2025. But there are two problems with this notion: Lake Sullivan is the headwaters of the Verde River, and the sentence about “going dry by 2025” was removed in later versions of the report.

Naysayers will also focus on one drought year of statistics and often fail to discuss flood years and the recharge that occurs in those years and in plentiful rainy seasons like this past summer.

Whitmer points out that precipitation levels this monsoon season have been significantly above average, which has resulted in significant increases in the flow of the Verde River at the USGS stream flow gauges at Paulden, Clarkdale, and Camp Verde since July 1.

When asked if a one year synopsis of water supply in Yavapai County was a fair estimate, Keith Nelson of the ADWR said, of the most recent state model, “The model calibration is explicitly based on available data. If data indicates natural recharge has occurred, model parameters, including natural recharge, are adjusted to fit the data in a systematic and objective manner. For example, 2002 was a very dry year, so the model is calibrated to data that limit natural recharge. On the other hand, 1993, 2004/2005, and others, were relatively “wet” periods. Consequently, large rates of natural recharge input into the model, to fit available data (minimize model error). We simulate stresses to the aquifer in a seasonal manner. I think what you are saying is that each year should be treated independently, which is the way I calibrated the model.” Modeling Report 14, and others, can be found at new.azwater.gov and azwater.gov.

But the civic planners on the southwest side of Mingus Mountain are thinking long range and have invested money in an intergovernmental agreement known as the Big Chino Water Ranch (BCWR). The City of Prescott is a 54.1% partner and the Town of Prescott Valley a 45.9% partner in the BCWR. If the plan works, the towns will get about the same percentage of shared water and the contract states that they “could share” with Chino Valley in the future. They have also purchased ranches north of Prescott and Chino for use in aquifer recharge. Chino Valley has also acquired water rights in the Big Chino Sub-basin but they are not currently part of the BCWR project.

Imagine a 39-inch wide pipe running from Prescott to the Big Chino Sub-basin 30 miles north of the city. Neither town can afford to hire a contractor, yet.

The Cadillac design would cost close to $300 million, unless some of the gold plate is shaved. And planners admit there could be cost savings. For instance, the pipe may not have to be 39 inches wide. It could be narrower to meet needs and a narrower pipe over 30 miles, and cheaper pumping stations are of course cheaper. Regardless of price, the new water pipe and recharge plan would insure adequate water supplies for more than a century.

The investors do not have all the financing but there have been visits to town by investors from Saudi and Australia because buying into American utilities is considered a safe investment.

It is important to note that all bodies of water in Arizona are “connected.” (see ADWR map) And the Arizona Supreme Court has made two interesting rulings: groundwater and surface water are legally connected under certain circumstances, and surface water is a constitutionally protected, vested property right. So, it will be of critical importance for Yavapai County residents to see the conclusions in the report due out in 2020.

“There have been many USGS studies over the years and there have been many consultants doing studies in the little and big Chino area over the years and many different groups that have studied water in the area,” said Macy.

“The info that these groups have gathered is currently being put into a computer simulation called ‘the groundwater model.’ It will be used to understand current pumping and future pumping and the effects that the pumping will have on ground water systems.” Many water reports can be found at pubs.usgs.gov

“Prescott Valley and Salt River Project jointly fund the groundwater model project with Prescott. Prescott is the fiscal and contracting agent, per the agreement,” said Munderloh. The report was due in 2020, therefore it is 5 years later arriving to a town that never watches over its consultants – Prescott Valley.

This will be the best way scientists will be able to say if current ground water use is sustainable over time and whether residents on the southwest side of Mingus Mountain are truly running out of water over time. And if The Adjudication lawsuit is ever settled, Arizonans will learn who really owns the water rights.

Views: 6